When Osama Bin Laden was located in a compound in Pakistan, the President of the United States charged Bill McRaven with executing a plan to capture or eliminate the mastermind behind the 9/11 attacks.

McRaven came up with two plans. The first was simple. Bomb the shit out of the compound and be done with it. The second was riskier, but had greater rewards. Send an elite strike team of Navy SEALs to eliminate the target and confirm with DNA testing that Bin Laden would no longer be a threat to our nation. Naturally, the president elected the second option.

This left McRaven with a problem. How do you get an elite strike force into Pakistani territory without being detected? A team of intelligence officers examined the problem from every angle, and eventually landed on sending in the SEALs on a heavily modified Black Hawk helicopter with radar absorbing materials and noise reduction technologies. The choppers were commonly referred to as Stealth Black Hawks.

However, McRaven objected to this plan. He argued that the Stealth Black Hawks were known for their failure rate, and they did not consistently hold up to the rigors of war. He felt the machines posed an unacceptable amount of risk to his team. He was overruled by his superiors. This left McRaven between a rock and a hard place.

He didn’t want to endanger his men any more than was necessary, but a general had given him orders to do just that. A man who literally wrote the book on American Special Operations now had to do the opposite of what his instincts were telling him. He accepted his orders and embraced the dichotomy of control: control what you can, ignore what you can’t.

Down near Fort Bragg in North Carolina, the United States military created an identical compound of the one the Navy SEALs would eventually storm. The soldiers selected for the mission would rehearse daily, flying in on two stealth choppers and practicing the plan.

However, McRaven never really allowed them to merely “follow the plan.” Nine times out of ten, he would alter the challenges of the mission during practice. Sometimes a group of Pakistani soldiers would appear on the street outside the compound. Other times there were more soldiers inside the compound than originally thought. McRaven would sometimes cut the soldiers’ ability to communicate through comms.

The most consistent curveball he threw at them? Helicopter failure.

According to the SEALs, McRaven would throw that training stipulation into practice around 50% of the time. It was a joke among the SEALs - who was riding the deadbeat chopper this time? Engine failure, losing a chopper before the mission began, rotator problems, each time these things happened, the SEALs would have to improvise on how to best continue the mission. They enfolded helicopter failure into their muscle memory.

Everybody knows how the mission turned out. I’ll never forget watching Obama give an emergency press briefing informing the world that the ultimate villain had finally been brought to justice.

But, what’s less known is how close we were to never receiving that moment. The mission was almost doomed from the start when one of the choppers malfunctioned and crashed outside of the compound. Luckily the SEALs survived, executed the mission, blew up the broken helicopter, and flew out on the spare chopper.

They didn’t miss a beat. McRaven’s preparation for the worst was damn near prescient. They were so well prepared for something to go wrong, that when it did, it was as if the problem was part of the plan anyway.

It’s the kind of training teachers need.

Preparing for the Worst

Teacher preparation programs in public universities never really prepare you for problems on the job. They focus on the ideal situation. In classes focused on pedagogy, you might sit down and discuss lofty ideals for how a student should intellectualize the main thrust of their synthesis essay. I don’t even know what that last sentence meant, but it’s exactly how some of my education classes felt when I was preparing to be an English teacher.

We’d sit down and discuss the merits of one activity over another. We’d practice the importance of modeling the activity before doing it. We’d discuss how a certain activity would relate to Bloom’s Taxonomy. Was the student creating? Evaluating? Or merely memorizing. A savvy student might suggest incorporating a peer assessment rubric into the activity to increase student to student feedback. A professor would go “oooh” and “aaah” when they heard that; peer to peer feedback is just so chic.

Unfortunately, that savvy college student has no fucking clue what to do when a student decides to take that peer assessment rubric and rip it into shreds. Wait a minute, that kid is supposed to talk respectfully to his classmates while discussing how to eliminate the passive voice from their essay. But… wait… oh god, now the kid is screaming that he doesn’t give a fuck about the essay… could we just… oh boy, now he’s picking up a chair… c’mon man, just please fill out the peer assessment rubric…

Discussion of excellent teacher practice is nice, it just doesn’t mean much without the backbone of classroom management. I spent hours in college classes discussing writing theory and how best to improve a student’s grammar. When I went to get my masters in Physical Education, I spent an entire semester learning the different muscles and bones of the body, “phalanges” is a fancy word for your finger and toe bones if you care to know. But between both of my education degrees, I spent maybe three classes - as in three 45 minute classes - discussing classroom management strategies.

It was like learning proper sprint technique before you knew how to crawl.

I learned how poorly prepared I was when I started student teaching at Newark High School in Delaware. When my cooperating teacher handed me the reins of the classroom, I had dreams of covering George Orwell’s 1984 novel. One of my early classes went a little like this…

“So as you can see, when George uses the term doublespeak, what he’s doing is -” Students ignored me with their conversations. “Excuse me please stop talk-” student conversation continued. “Guys. Please stop!” They stopped for a second, then a student produced a Kermit the frog doll with an electric voice. “Hi! Miss Piggy.” Where the hell did that come from? I confiscated the frog, but the electric voice wouldn’t stop talking, “Hi! Miss Piggy. Hi! Miss Piggy,” and I didn’t know how to turn it off. I went back to the student,

“Turn it off.”

“Nah man, I don’t know how.”

Twenty-one year old me sighed exasperatedly, as “Hi! Miss Piggy. Hi! Miss Piggy. Hi! Miss Piggy” started to beat a headache into my skull. I did everything I could do to stop myself from ripping the damn thing in half. I eventually settled on throwing Kermit down the hallway as he continuously tried to greet his girlfriend. The kids laughed in uproarious delight.

“Alright.” I say as I finally get back to the top of the classroom. “Now, I think we were discussing doublespeak - hey! Can we please stop talking!” Student gossip continued unabated.

This was a standard experience during my first month of teaching. I would try to run a lesson, and then students would routinely interrupt me. Either through conversation, phones, or some other student fuckery, they would derail the hours I spent lesson planning the night before. If you’re wondering what my cooperating teacher instructed me to do, don’t worry, he didn’t. When he handed the classes over to me, he shook my hand and said he would be in the library. I proceeded to flounder in a classroom for the next three months with zero professional help - I wish him ill. With that said, I decided I needed to watch a professional teacher teach.

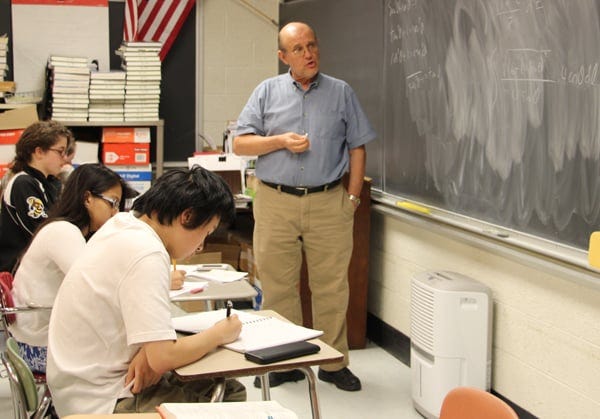

In a school of 1,200 kids I asked as many of them as I could who they thought ran the tightest class. A teacher by the name of Mr. Koliss kept coming up. When I asked a student why he thought the man ran a tight class, the kid said, “I don’t know man, you just wouldn’t want to mess with him.” That got me curious. I eventually sat in on Mr. Koliss’ class and witnessed a world class demonstration on classroom management.

The students walked in, sat down, and quietly got to work. I noted that many of his students were the same ones that would have loud conversations in my class. An old heavy set man with glasses trudged around the front of the room. He offered friendly advice to students struggling with the do-now. He didn’t seem all that intimidating. Then a late kid tried to slink in through the classroom door with a bag of McDonalds. Mr. Koliss looked up and immediately started not quite yelling. His tone was a double whammy of stern and uncomfortably loud.

“So let me get this straight. You walk in late with a bag of McDonalds.” The kid ducks his head. He knows he’s caught. “You’re missing the do-now which is going to hurt your grade. And you think you’re going to eat in here? I can’t wait to have a conversation with you mother about this.” Again, his voice is mean and loud - not out of control - but uncomfortably sharp. “You can go ahead and put that food you’re not going to eat on my desk. Then I’m going to think about what to say to mom.”

The kid left his food on Mr. Koliss’ desk and walked to his seat, head bowed, tail between his legs. The rest of the kids watched the exchange, but didn’t react much. Most of them got right back to work. One girl rolled her eyes and quietly muttered, “always with the calling the mom.”

The exchange fascinated me. When they did decide to mention consequences, my professors had always instructed me and my classmates to take kids aside and tell them their punishments in private. Never shame a student in public, that was a huge no no. Seems Mr. Koliss felt different. I noted that while he was not quite yelling at the late student, he was communicating his expectations with the rest of the class - walk in late with food, enjoy a reduction in your grade and a phone call home. He was stopping future battles while dealing with the one at hand.

I also noted there was no room for excuses, the student didn’t even have the chance to say why he was late or that he didn’t have the chance to have breakfast. My professors had always recommended you give the students the benefit of the doubt. Seems Mr. Koliss felt differently. He ruthlessly executed his expectations, and he immediately enforced consequences when they weren’t met. He reminded me of my old award winning band teacher.

After spending more time in the school, I slowly learned that despite Mr. Koliss’ strict demeanor, the student body loved him. His AP calculus class routinely passed the AP exam in high percentages. I also learned he was in his 40th year of teaching. The Christiana School District awarded him “Teacher of the Year” the year I observed him. It was his third time winning the honor.

Here’s the point. Mr. Koliss knew all the pedagogy slop professors force feed their college students. He knew how to apply the Zone of Proximal Development, and he understood Bloom's taxonomy. I hold these learning theories in low regard, not because they’re not important, but because their importance pales in comparison to basic pragmatic classroom management policies.

There should be entire college courses dedicated to helping newbie teachers practice what to do when shit goes sideways. Like Bill McRaven training his SEALs, teachers need to walk into a classroom with the assumption that things are going to go wrong, and they need a well practiced tool kit they know how to use the moment kids start derailing the class.

Imagine if the SEALs hadn’t practiced helicopter engine failure before they experienced it? Imagine they had just rehearsed perfect scenarios? What if the mission was based on theory? Osama might still be running free and we might have had a helicopter full of dead Navy SEALs. This is essentially what’s happening to teachers. The profession has a 50% turnover rate nationwide, and you can dial up that number to 70% for Title I schools. Teachers consistently cite challenging student behavior as a reason they leave the profession. Most teacher newbies are walking into the classroom without body armor, and when the bullets start firing, we lose over half of them.

My advice to all those creating the pedagogy curriculum at the university level. De-emphasize the theory. It’s lovely. It’s important. It doesn’t do dick when kids talk over you. Emphasize meaningful classroom management policies. Relentlessly practice them repeatedly. Never allow a practice lesson to happen without something going wrong. New teachers need this preparation.

There are good, young people who will leave my profession in less than 4 years.

I’d like to have more of them stick around.

*4 years ago, I read Kevin Kelly’s world breaking article, “1000 True Fans.” The gist of it goes like this. Create a following of people who become fans of what you do. Be so damn good at what you do that people want to give you money so you continue doing it.

Here’s what I do. I teach, and I write stories about it.

I hope you consider becoming a paid subscriber… though if your initial reaction to that is, “fuck off, I’m just here to read,” then rock on. Fit To Teach is free to all.

fellow hs teacher here (AP English 4, in Chicago 😅) . just wanted to say it’s refreshing to find someone who gets both the chaos of the classroom and the quiet magic of expressing it on the page. you’re delivering it all with great literary style. Love!

Great article. I was under the impression that education degrees spent a lot of time on classroom management.

More disturbing than the number of minutes, though, is the fact that what they were teaching you in that time is wrong. If they start doing simulations where a student acts out, and then the other 25 students stay calm and quiet while you take the offender out into the hallway for a quick impromptu therapy session (which he responds to by tearfully thanking you for helping him discover his love of literature, of course)... I'm not sure that's going to improve early teacher retention rates.